Why Jiu Jitsu—Not Psychedelics—Is the Real Hero In My Life

How meeting myself on the mats makes the lessons from plant medicine (and life) stick

Want to listen to this post? Tune into the podcast version here.

A discretionary note for readers: In this piece, I talk about sexual assault.

In journalism school, one learns several important rules of the craft in the name of truth, accuracy, and objectivity. Some are critical and ought to be adhered to: Take notes. Do your research. Record everything. Interview as many subjects as possible. Others are a bit more open to interpretation (though I’m sure the old-fashioned among you would argue this point). I remember several instructors repeating that a writer “should never become part of the story.” I haven’t always been very good at adhering to this rule.

In my books, I’ve been very open with readers about how cannabis and psychedelics have played an important role in helping me overcome depression and PTSD. (I’m old-fashioned about a few things, but I think there’s a place for vulnerability in journalism.) I’ve also written about how psychedelics alone can’t solve our problems. They are but a tool in a toolbox full of other useful implements begging to be used in conjunction with one another. Imagine trying to repair a car engine with just one tool. Having grown up in a family of mechanics, I can tell you that it wouldn’t go very well.

Even with the right equipment, tools need to be oiled, serviced and sharpened to be their most effective. If psychedelics are the tool in question, preparation is the grease, integration is the maintenance, and community is the grindstone. Many psychonauts laud yoga, meditation, and breathwork for the space they create within to prepare and integrate a psychedelic experience, and while I’ve certainly found these practices helpful, for the most part, they are done in solitude. No practice has offered me more in the way of these three critical components than jiu jitsu, a sport that a younger me would never have imagined trying, let alone becoming obsessed with.

If psychedelics are the tool in question, preparation is the grease, integration is the maintenance, and community is the grindstone.

What is Jiu Jitsu?

jiu-jitsu

/ˌjo͞oˈjitso͞o/

A Japanese system of unarmed combat and physical training; from the Japanese jū, meaning “gentle,” and jutsu, meaning “art” or “skill”

Brazilian jiu jitsu or BJJ is a ground-based martial art that utilizes grappling and submission holds. Where better-known martial arts such as Tae Kwon Do and Muay Thai focus on strikes and kicks, modern jiu jitsu pulls from other martial arts such as judo and Japanese ju jutsu and swaps punches for joint locks and chokes. It involves carefully stringing together a series of movements to manipulate the body and limbs of one’s opponent until they submit or “tap out.” A major principle of jiu jitsu is leverage. The goal is to apply force at specific leverage points such as the legs, arms, or (my favourite) neck to generate a tap. It’s technical, tiring, and constantly tests one’s ability to keep going in the face of what feels like imminent failure. It is as much a mental game as it is a physical one and is often described as akin to human chess. In a sport with five belt ranks (from lowest to highest: white, blue, purple, brown, and black), it’s been said that just 10 percent of new jiu jitsu students stick with it long enough to earn a blue belt. Of those, just one percent earn the highest rank, a black belt—a feat that takes most practitioners at least 10 years to obtain.

It might be counterintuitive to some that this seemingly violent sport has become my number-one psychedelic support system, but jiu jitsu isn’t inherently aggressive—in fact, the first thing I learned in jiu jitsu was how to walk away from a fight. (Studies show that jiu jitsu practitioners report lower levels of aggression than practitioners of other martial arts). It’s less about the techniques I’ve learned during the hours I’ve spent attending class, and more about what I’ve learned about myself while having my face pressed into the mats by a (usually much larger) training partner that has me so convinced jiu jitsu deserves more credit in my life today than psychedelics. While my experiences with medicines like psilocybin and ayahuasca have undoubtedly been the catalysts for profound shifts in my life, the maintenance of these massive changes isn’t as sexy as the peak experiences that generated them (unless, of course, you think learning to get comfortable beneath the intense pressure of a sweaty opponent is sexy).

The effects of psychedelics are powerful, but they don’t last forever. The insights we receive only feel crystal-clear for so long, and unless we’re putting those lessons to work, before long, they fade away. It’s through my commitment to the practice of jiu jitsu that I consistently face the parts of myself I’ve met repeatedly in psychedelic journeys that want to give up, tap out, and throw in the towel – but also the parts that want to crawl back to my feet, stick it out, and create opportunities for myself to come out on top.

The Complementary Neurochemistry of Psychedelics and Jiu Jitsu

Let’s go back to that tool analogy. It wasn’t always obvious to me, but in my experience, psychedelics and jiu jitsu are like sockets and ratchets: best when used together. I go into incredible detail explaining how this has been true in my own life below, but for those of you who’d prefer a side of evidence with my very generous helping of personal experience, here’s some science. Consider the effects psychedelics and jiu jitsu have on the brain’s neurochemistry:

Classic psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD, and DMT trigger physiological responses associated with serotonin, a neurotransmitter known for its role in stabilizing mood and promoting feelings of well-being, opening a window of neural plasticity where new connections can be made in the brain. Some psychedelics, such as mescaline and MDMA, stimulate receptors of another type of neurotransmitter, dopamine, which is tied closely to reward, motivation, memory, and attention. MDMA also triggers the release of norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline), which plays a role in the body’s stress response. The psychedelic dissociative ketamine generates neural plasticity by increasing levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, a protein that plays a role in the growth and maintenance of neurons.

Many of the same neurotransmitters, hormones and proteins at play during a psychedelic experience are impacted similarly by jiu jitsu (and physical exercise in general). Jiu jitsu stimulates serotonin production in a few ways: first, through strenuous physical exertion. Training isn’t the only thing that stimulates the release of serotonin. It’s also elevated by the strong bonds shared with teammates. At the same time, learning—and successfully executing—techniques and submissions stimulates the release of dopamine, providing an intense sense of reward. Jiu jitsu also modulates the release of norepinephrine to reduce stress. And while jiu jitsu certainly won’t get you high the way magic mushrooms will, the overwhelming release of endorphins and BDNF after an hour and a half of rigorous training can come pretty close. (That “runner’s high” feeling isn’t just for runners.)

The Grease: Preparation

Like a journalism instructor might tell you to keep yourself out of the story, the legions of wellness coaches on Instagram will tell you that preparation is one of the most important parts of intentional psychedelic journeying. As cringey as some online coaches are, I’m not about to disagree with them on this one. Preparing for a psychedelic journey is as much about having the right mindset as it is about determining where and with whom to travel.

Ask a psychonaut (or coach) for advice ahead of a deep medicine journey and you’ll probably hear something along the lines of “surrender to whatever comes up.” In my early psychedelic experiences, this was a tough thing for me to wrap my mind around, because I wasn’t sure I had what it took to make it through the challenging material that would surely arise. At the height of my depression and PTSD, my fear of failure consumed everything; even my quest to get better. What if I failed at psychedelics? What if nothing happened? Or worse, what if, when posed with the choice to move past my depression or remain in the comfort of my sadness, fear of the unknown drove me to choose the latter?

Thankfully, because I believed there was no possible way it could have been worse than being depressed, I leapt blindly into the unknown and surrendered to everything in those early experiences, no matter how ugly. With that leap came a sense of confidence and freedom to do all the things I had ever thought I was incapable of. I know now that I have what it takes to do hard things because of the plentiful evidence that I can overcome even the most ingrained self-limiting beliefs.

Like this one: I used to believe I wasn’t athletic. As a kid, I was lousy (read: disinterested) in team sports, and I wasn’t flexible, graceful, or wealthy enough to do dance or gymnastics. Martial arts were never on the table as my parents are staunch pacifists. (“Mennonites don’t fight, Amanda.”) As a young adult, I relegated myself to hours of mindless cardio in the gym, with no specific goals other than blowing off steam and staying in shape. I tried to enjoy it, but mostly, I hated every minute.

I didn’t find jiu jitsu until my late 20s. Around the same time I began to use psychedelics to treat my mental health issues, my partner, Eric convinced me to try a class. It was jarring to learn an activity that required so much moving on the ground. Learning the basics was tough, but not as tough as grappling with the lifelong doubts I had about my athletic ability, especially when I struggled to pick up a new technique, or when my sense of control evaporated while sparring with a higher-ranked training partner. During my first year, I often thought of giving up, and cried hot tears of frustration on the drive home from class more times than I’d like to admit.

Eventually, I began to understand that bearing the weight of higher-ranked training partners—and my own fear of failure—was exactly what I’d signed up for. It was baked into the sport and very much something to be endured in order to move on to the next level: blue belt. “White belt,” my instructor used to say, “is about survival.” Every class was another opportunity to try (and fail) again, and with time, I became less afraid of failure and more resilient to pressure—both the physical pressure from my partners and the mental pressure I was so used to putting on myself.

After almost two years of regular practice, a couple of of local competitions, and earning my blue belt, I took a long break from jiu jitsu to write my first book. Then the pandemic happened, and I didn’t return to it again until June 2022, this time training no-gi (without the heavy, goofy-looking pyjamas). Today, I train jiu jitsu nearly every day, lift three times a week, and go for daily walks or runs. Moving my body is like brushing my teeth and making my bed: a non-negotiable part of my routine. It’s hard to imagine what my life might look like had I continued to subscribe to the belief that I was not athletic. Choosing to throw it away has transformed my mind, body, and quality of life in every possible way.

So how does all of this contribute to preparing for a psychedelic experience? Committing myself to this martial art has taught me that I can withstand physical discomfort for long periods of time, I can remain calm in overwhelming situations, I can problem-solve under pressure, I can set an intention and stick to it, and I can overcome even the most deeply ingrained self-limiting beliefs. I’ve become so comfortable with being uncomfortable that the phrase “surrender to whatever comes up” no longer strikes fear into me, it excites me—because it’s become part of my regimen. I’m surrendering to whatever comes up six days a week, and believe me when I say, the skills are transferrable.

The Maintenance: Integration

You might have heard psychedelic evangelists say things like, “One psychedelic trip is like ten years of therapy!” This phrase leaves me with more questions than answers. Is ten years of therapy the bare minimum before one’s trauma becomes subdued? Are we suggesting that therapy isn’t that effective, and if so, why are we making this comparison? Are you telling me I should just skip therapy altogether and take a hero’s dose in silent darkness?

If you ask me, alone, neither ten years of therapy nor a single psychedelic experience is enough to rewrite the stories that live in our bodies. Insights, whether received in therapy or in ceremony, are just information until we put them to use. It is through the deep and challenging work of integration that we come to understand the insights we are given and where they can be applied in our lives. I can attend therapy for several years but if I don’t do anything to alchemize the information I’m given, nothing changes. The same is true for psychedelic experiences.

Journaling, meditation, and prayer are all helpful modalities for integration that can be woven into one’s daily routine, making them great options for regular mindful reflection. But if, like me, you’ve suffered some sort of physical trauma, working things out in your mind and even on paper might never feel like enough. My depression and PTSD were spurred by a sexual assault. As I used psychedelics to move through my symptoms and eventually get better, attaching integration to an embodied practice like jiu jitsu was a complete and utter game-changer for me—though at the time, I didn’t know I was doing it.

Here's the thing: I could talk about my experience ad nauseam in therapy and make peace with it (even forgiving my attacker) while under the influence of powerful drugs, but once the afterglow had faded, the consequences of being physically violated still felt present in my body, like a dull tingling or a light ringing in my ears. Sometimes it was more overwhelming, as if someone had scrawled the word “RAPED” across my forehead in permanent marker for all to see. In arming myself with the art of jiu jitsu, I was able to rewrite the story once and for all.

It wasn’t until a few months ago while reading the book Transforming Trauma with Jiu-Jitsu by Jamie Marich and Anna Pirkl that I began to understand how critical it has been to my healing. “The whole practice of jiu jitsu is a very interesting lens through which we can discover humanity and self-love,” says Alex Ueda, a black belt and jiu jitsu instructor quoted in the book. He goes on:

“When you practice it enough in a controlled environment, you realize you will survive and you develop an analytical approach to the things that would make you normally panic outright.” Through consistent practice of this process, according to Alex, you can learn the most important lesson of all—you were always worth defending.

Laying on the beach under the warm May sun, I read that last line over and over again until tears formed in the corners of my eyes. Then a big grin spread across my face. I knew I didn’t need to say those words out loud for them to be true because they were already true in my body.

It wasn’t immediate, but eventually, jiu jitsu took the feelings of unworthiness at the root of my depression and put them in a chokehold, suffocating them every time I landed a new takedown or finished a different submission. It taught me to quell fear with curiosity and perfectionism with practice. It taught me that I was worthy. Beyond the opportunity it gave me to rewrite the story in my body about being assaulted, it allows me to learn and re-learn the lessons I receive from psychedelic plant medicines, and from life itself, over and over again.

The Grindstone: Community

Author and motivational speaker Jim Rohn said that we are the average of the five people we spend the most time with. The people we surround ourselves with can keep us sharp or make us dull. They can encourage us to dig deep and move past our limitations or they can coddle us when we spiral.

Jiu jitsu attracts people of all ages from all walks of life, often for very different reasons. Some people come to stay active. Others do it for the thrill of competition. Many women join to build confidence and self-defence skills. A few pick it up because they watch the UFC and want to see what “this jiu jitsu thing” is really about. Whatever the reason, it doesn’t take long before you become friends with all of them. After graduating from college, I thought my friend group would shrink. I never expected to find a new one, especially in a city as notoriously hostile as Vancouver, but I learned quickly that it’s hard not to become friends when you’re sweating into each other’s eyeballs. If the culture in a gym is well-nurtured, the camaraderie is almost immediate.

There’s another reason friendship happens fast: jiu jitsu doesn’t work in isolation. Learning new techniques and honing existing ones requires collaboration from coaches and training partners. It takes an open mind, and a willingness to give and receive feedback without taking things personally. And when we spar in preparation for competition, it requires that we push each other…. hard. It means during the last minute of the round, we don’t let up; we dig deep, scraping the bottom for whatever energy we can muster and encouraging our training partners to do the same (even at the risk of getting caught in an arm bar or leg lock).

It’s hard not to become friends when you’re sweating into each other’s eyeballs.

The mutual sharpening that happens on the mats isn’t just about building mental resilience. There’s another element of jiu jitsu that doesn’t get enough attention, perhaps because it’s an awkward topic in such a male-dominated sport: non-sexual intimacy and touch. Studies show that non-sexual touch releases oxytocin or “the love hormone,” increasing feelings of trust, bonding, and empathy.

It’s a special thing to feel safe in the grip of your training partner even when they are trying to break your arm. Surrounding myself with people who I can trust not to snap my limbs when I mindlessly put them in the wrong position means I can also trust them when I’m struggling with something more personal. It’s no wonder the people you train with eventually feel like family.

Just as it is impossible to do jiu jitsu alone, one cannot expect to reap the benefits of the insights they receive living life in isolation. My teammates and I hold each other accountable. We check each other’s egos. We are like mirrors, reflecting back what’s working and what’s not, and offering new insights where old ones could use a little refreshing. And of course, the cornerstone of any good community: we know how to have fun.

Here are just a few of the insights that are reinforced daily on the mats and honed by my teammates:

Stay calm and slow down

Be present

Do everything with intention

Keep an open mind

Learn to rest but don’t give up

There are no shortcuts

To find out, you must fuck around

Respect each other

Respect yourself

Respect your environment

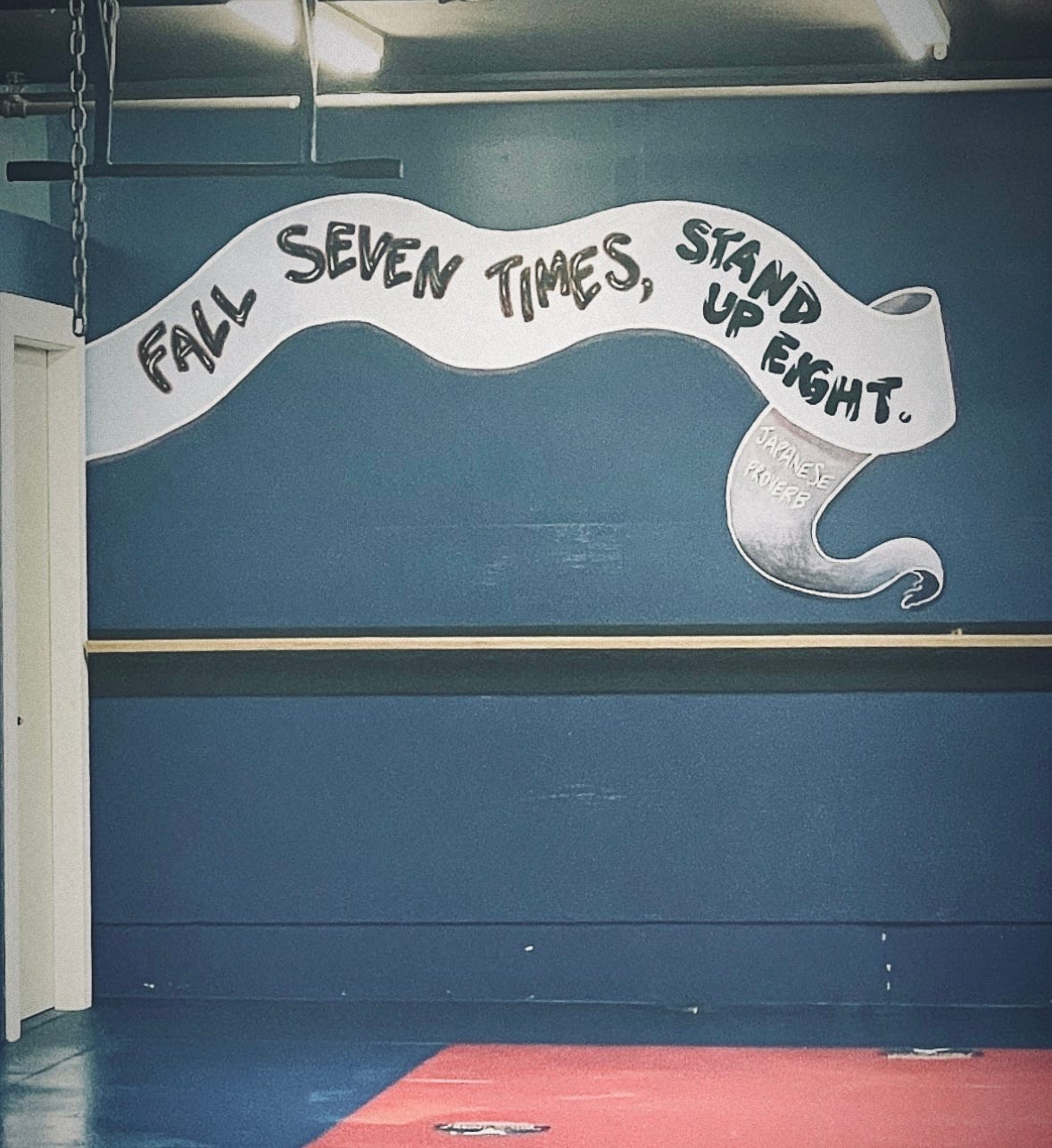

Fall Seven Times, Stand Up Eight

There’s a Japanese proverb painted on the wall of one of the first gyms I trained at that reads: “Fall seven times, stand up eight.” During my first year of training, which involved a lot of falling, it sometimes felt like those six words were mocking me. Today I’m more appreciative of the simplicity of their message.

The practice of jiu jitsu and the intentional use of psychedelics both beg for the same thing: that we keep going; that we support one another; that we humble ourselves, shed what doesn’t serve us, and welcome new perspectives to improve the places and spaces we occupy. They require us to take stock of a situation and make use of what’s in front of us—and what is within us. Both are accepting of failure. They make room for it, clearing away the mess of the mind and bringing clarity, flow, and a sense of calm within the chaos. They empower us with the vitality and the confidence to fight back against the narrative that we don’t have what it takes, even when it feels like we’re stuck. They encourage us to contend with the rules we’ve been following our whole lives and create new ones.

One of my less old-fashioned journalism instructors had this to say about rules: we learn them so that we can break them. I could have spent the last 3,400 words interviewing world-class practitioners, coaches, and scientists about jiu jitsu and psychedelics, but I’m not sure that would have accurately conveyed my gratitude for these tools and the grandiosity of their impact on my life. They have helped me find my edges and face my fears, surrendering to and even embracing discomfort to come out on the other side, transformed.

It's hard to pick a favourite Terence McKenna quote, but this one comes close because it speaks to the power of fearlessness—or rather, of being afraid and doing it anyway—a feeling that still comes up when I’m about to roll with a superior competitor or ingest a hallucinogen:

“Nature loves courage. You make the commitment and nature will respond to that commitment by removing impossible obstacles. Dream the impossible dream and the world will not grind you under, it will lift you up. This is the trick… This is how magic is done. By hurling yourself into the abyss and discovering it’s a feather bed.”

In my case, the abyss isn’t quite a feather bed—it’s a set of mats and a room full of sweaty grapplers.